February 25, 1964, Cassius Clay defeats Sonny Liston:

I've spent my life avoiding the temptation of idolizing athletes, rock stars and movie stars, or anyone else, for that matter. But I had one weakness: Muhammad Ali. He was a true giant of the 20th century, a man who transcended sports, who dwarfed anything else captured by the media, who personified grace and courage, brutality and poetry.

It's a challenge to imagine a world without him, not unlike the shocking death of John Lennon in December 1980, a few days before my 18th birthday. It's now a profoundly altered world that I live in. I should be in better shape to handle this one.

About five years ago I was on an annual getaway in Arizona, taking in some spring training baseball. I want to say it was the Dodgers playing the Royals. It was an ordinary outing. The game dragged on. At some point, between innings, a buzz started to sweep through the crowd. We couldn't tell what the fuss was. And then it became apparent. I don't remember there being an announcement, but there might have been. Way down on the field, a bullpen car was making its way up the third-base/left-field line. Inside was Muhammad Ali. The crowd didn't cheer so much as chatter in awe. I couldn't see his face, don't even remember a wave, but I felt a profound sense of child-like wonder whoosh through my body. I gasped like a teenage girl watching the Taylor Swift take the stage. I sensed a unity with every other person in that stadium, a unanimous acknowledgment that we were being blessed by the mere presence of an other-worldly prince of peace.

It was a fleeting moment. I've never been able to re-create the feeling.

We have reviewed two documentaries about Ali in our short time in this spot. I previously told a version of that spring-training story and admitted that "I seem to never get enough of documentaries about" the man. The most recent one, "I Am Ali," is "an incredibly intimate portrait of the boxing legend," sifting through audio tapes of phone calls to his children and putting forth revealing interviews with wives, rivals, insiders. The other, from two years ago, is "The Trials of Muhammad Ali," focusing on Ali's conversion to Islam and his refusal to serve in Vietnam, as a conscientious objector.

Of course, the most memorable documentary is "When We Were Kings" (from the director of "Trials"), which chronicles the trip to Zaire by Ali and George Foreman and their entourages for their Rumble in the Jungle, one of the greatest fights ever. Watching the bout again last night, I was reminded that it wasn't just a cheap rope-a-dope exhibition by Ali. Rather, he came out in the first round firing combinations and stunning Foreman, who at the time was a veritable Hercules who had demolished Joe Frazier and Ken Norton and was expected to dismantle the 32-year-old ex-champ. As I watched the fateful 8th round tick down, my heart raced with anticipation of the final furious explosion from Ali, culminating in the sharp right that sent Foreman windmilling to the canvas, as if Ali had toppled a building with his fists; it was an upset as improbable as Buster Douglas' KO of the super-human Mike Tyson in 1990.

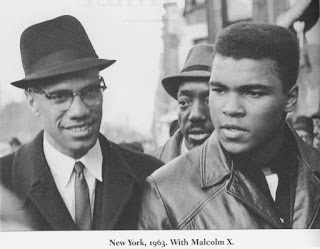

"Kings" sweats in the African heat, celebrating '70s black culture with the likes of James Brown and B.B. King. The exploration of ethnic heritage, with prominent black Americans connecting with their roots, is genuinely moving. For Ali, it seemed like vindication of his embrace of the Nation of Islam and his devotion to the separatist ideology of Elijah Muhammad. I was too young to be aware of his 1964 conversion to Islam and the renunciation of his slave name -- and the resulting cultural upheaval that he foisted on society in that turbulent decade. The world had never seen anything like him, and he refused to be silenced by the white media and power structure. When he resisted going to Vietnam ("No Viet Cong ever called me nigger") it thrust him into the political maelstrom and in sync with the Rev. Martin Luther King, who would speak out forcefully against the war one year before his assassination.

Ali spent his prime years as an athlete exiled from his sport and touring college campuses, honing his rhetoric, learning how to articulate his worldview. MSNBC aired "When We Were Kings" tonight, and the channel's coverage has been thorough all weekend. I saw a clip of Ali speaking at Harvard in 1975, a graduation speech that is difficult to track down online. A memorable line was a plea for selflessness over selfishness. Another reminder of how to be in the world.

Muhammad Ali was recognized (and idolized) in every corner of the globe, and he was as powerful a cultural force as any athlete or politician of the 20th century. He was Jackie Robinson, MLK and Michael Jordan rolled into one. In purely physical terms, he was the greatest boxer of any era. The combination of his incessant cockiness and his balletic ring skills made me swoon as an adolescent, just like it aggravated my angry father. Ah, anybody could fight that well with that reach of his, my dad would scoff. Rocky Marciano -- now there was a heavyweight. A paisan. Undefeated. He would have burrowed inside on Ali and destroyed him! Tell that to George Foreman, dad. To Sonny Liston. Joe Frazier.

Though I didn't realize it until well into adulthood, I have absorbed important life lessons from Muhammad Ali -- about race, about the idea of God, about social justice, about beauty and courage. My father was a bitter victim of the civil-rights and anti-war movements; I managed to escape his old-world vortex somehow, stumbling on occasional glimpses of what I assume to be enlightenment. My dad, who died 25 years ago, taught me many things. But so did Ali. He shook up my world.

Back to that day in Arizona. I think what was most important was the warm contentment I experienced, serenity amid a crowd of strangers. Ali's random appearance assured me that he was still in the world. After his death on June 3, 2016, I no longer have that assurance, that comfort of knowing he's somewhere in the ballpark, his mere presence magically merging thousands of souls into one soothing hum.

BONUS TRACK

Ali, the draft resister. "My conscience won't let me go shoot ... some poor hungry people in the mud for big powerful America." And, rapid-fire, to a white student: "You won't even stand up for me in America for my religious beliefs and you want me to go somewhere and fight but you won't even stand up for me here at home."

END CREDITS

The profoundly moving tribute to the legend (myth?) of Cassius Clay renouncing the racism of the South that he returned to from the Rome Olympics in 1960 by tossing his gold medal into the Ohio River. It's the deeply moving "Louisville Lip" from Catherine Irwin and Janet Bean of the alt-country band Freakwater:

"Whip the world, whip this town

Whip it into the river and watch it go down

Whip the world, your lashing tongue

Big man crying like babies from where the bee stung."

No comments:

Post a Comment